Anthology Unearths More War and More Valor

Previously Published in Consequence Magazine, 2018

By Amy Lou Jenkins

Two military veterans realized the experience of women in the military was hidden history. Their anthology complies first-person accounts of war experiences, so that silenced women finally have their say.

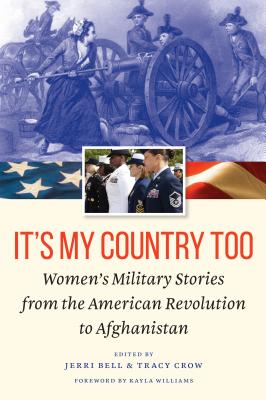

It’s My Country Too Women’s Military Stories from the American Revolution to Afghanistan, edited by Jerri Bell & Tracy Crow, Potomac Books, 2017.

Difficulties for Women in Every Era

Stories of women in the U.S. Military in It’s My Country Too follow a chronologic path of war across every era in United States history. The editors have collected women’s stories and, mostly, left it to the reader to draw meaning from the first-person accounts. Certainly, It's reasonable to assume that ‘treatment of women in the military has never been equitable.’ As the narratives accumulate through the decades of U.S. Military History, the assumption becomes fact. While the military didn’t create misogyny, the pressures of service and war and codification by the singularity of men in charge magnify the worst of our culture. When men dominate leadership, women suffer.

Women in the Military Contributions often Hidden

Military veterans Jerri Bell and Tracy Crow realized that they didn’t know the history of women who served before them: “Their stories had been overlooked, ignored, or dismissed as unimportant.” This collected history serves all who wish to understand the culture of the United States toward women who submit to noble sacrifice under subjugation. Every wartime account collected seems to evoke some consistencies of reaction in the reader: ‘Wow, these women in the military are amazing’ and ‘Shit (or choose your expletive), these women are treated as subhuman.’

Women in the Military Maligned

There’s more going on than women striving to be included in the ugly business of war. Women sought to serve the soldiers and to make a living. Companies in the Continental Army allow up to five “women of the Army” to serve the troops. They haul, cook, and serve food. They sew, pour cooling water over artillery, wash clothes, are detained as prisoners of war and court-martialed for desertion, and die without fanfare. For their service, they are called prostitutes, receive meager pay, and we might assume other indignities. If history remembers important people and events, the scarcity of records judges these women as insignificant. The few known women who participate in the Revolutionary War don't appear in most history books.

Early American History

Sally St Clare, a woman of color who served in men’s clothes as a gunner, is the first woman killed in action during the Battle of Savanna. Sara Osborn meets General Washington, who asks her if she "was not afraid of the cannonballs"? She replies, "No, the bullets would not cheat the gallows” and that “It would not do for the men to fight and starve too.”

Deborah Samson Gannet enlisted and fought as a man in the Continental Army. She left service after suffering a battle wound. She then became the first female paid speaker to lecture about military service. The written speeches that survive offer a veiled message. Her festooned speech conforms to her time, yet reveals an ornate sarcasm as she apologizes for swerving “from the accustomed flowery paths of female delicacy.” Slipped into dozens of apologies for her boldness is a contempt of men’s control over women as she subtly compares the tyranny of the Crown over the Colonies to men’s control over women. Women in the military, even when acting as men, returned to their background status. Stories from Revolutionary war women largely don't exist, so much so that their accounts fill only twelve of the 317 pages, with only two first-person accounts. Nonetheless, they represent those whose history is lost.

Civil War Times

The Civil War offers more voices, mostly by way of unpublished and self–published manuscripts. Here the anthology begins to collect first-person accounts.

Harriet Tubman, speaks through an archived interview about a harrowing  river crossing that terminated with her taking a hundred “contrabands” to the recruiting office to be transformed from newly escaped slaves to enlisted Union Soldiers. In four years of such service, she receives only twenty days rations from the government and small amounts of money to pay scouts. She raises money and sells interviews to continue her work. Her attempts to claim pay and pension failed.

river crossing that terminated with her taking a hundred “contrabands” to the recruiting office to be transformed from newly escaped slaves to enlisted Union Soldiers. In four years of such service, she receives only twenty days rations from the government and small amounts of money to pay scouts. She raises money and sells interviews to continue her work. Her attempts to claim pay and pension failed.

More covert women emerge as consistent fixtures on both sides of the war. Accounts of female Union and Confederate spies and soldiers appear without editorial comment about right and wrong. Women’s service lives are presented in their complexity. Women glorify war, boldly participate in the system that promotes inequities, and they act with bravery, skill, slyness, and viciousness. Mary Bowser serves as a slave/spy in the household of Conference president Jefferson Davis. Dr. Mary Edwards Walker’s covert actions include counseling soldiers to refuse unnecessary amputation. Her vulpine counsels are offered within a complicated power structure; she serves as an unappointed assistant to the male physician who voluntarily shares a portion of his salary.

Spanish American and WW I Era

During the Spanish American War, more than six female physicians serve as contract nurses. While slow advancements in women’s positions begin to appear in accounts of service, the assumption of the lower value of women stands firm. Loretta Perfectus Walsh becomes the first woman to enlist officially in the US armed forces. In World War One, women have more official status, especially as nurses. Accounts of respect from men begin to pepper the narratives of some women, while African American women are permitted to enroll in the Army and Navy Nursing Corps. Women in the signal corps have to purchase their uniforms. All women have lower pay and less authority than men of the same rank.

World War II and Korean War Era

Through WWII and the Korean War, women contribute along more official lines but are never equal. Women routinely suffer indignities such as having snapshots, of their face and figure from the front and back. The snaps determine work assignments, to some extent. Even if snapshots determine men's assignments, the connotations for women are sexual. Josette Dermody Wingo teaches men to shoot down enemy aircraft and then uses the GI bill to complete a master’s degree. She writes and publishes about her experiences. More women begin to publish and archive their personal stories. Consequently, they preserve a wider spectrum of personal memoirs including more from women of color.

Women Get the Shaft and Fight On With Valor

While no overarching narrative analyzes the meaning of these stories, through-lines do appear in the accumulated details. After every war, the military institutions revert to believing that women’s usefulness is a wartime fluke. The real military doesn’t need women—except for nursing and domestic functions. Women who serve are “not nice.” Not-nice women deserve what they get. Female soldiers have few mentors. Some male soldiers value women in service. Until recently, women were kicked out of service when wars ended. Scholars can find more threads to unearth and most will tug at the reality that women get the shaft officially, unofficially, and literally.

Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine worked to have women serve as permanent members of the Navy. She testified before the House in 1948 after learning of off-record executive sessions that sought to oppress women by placing them in reserves with the indefinite recall to active duty. Her speech moderates the degree of unfairness to Navy regulation because Smith held a position of power. Women can now have Navy careers.

Tailhook

The path toward equality feels long and narrow through the accounts of more modern wars. In 1991, Paula Coughlin endures the long-held tradition of the gantlet at the Tailhook Naval Convention. After her senior officers were unwilling to address her molestation complaints, she addresses the media. Public outrage prods an investigation, but male colleagues shun or harass her. Most Navy women didn’t offer public support. Coughlin resigns her commission in 1994. This history emboldens another through-line where women sacrifice themselves in war and peace.

The path toward equality feels long and narrow through the accounts of more modern wars. In 1991, Paula Coughlin endures the long-held tradition of the gantlet at the Tailhook Naval Convention. After her senior officers were unwilling to address her molestation complaints, she addresses the media. Public outrage prods an investigation, but male colleagues shun or harass her. Most Navy women didn’t offer public support. Coughlin resigns her commission in 1994. This history emboldens another through-line where women sacrifice themselves in war and peace.

Linda Bray leads troops in combat, on successful missions in Desert Storm, her career was then thwarted by injury and a bad evaluation. Mary V Jacocks commands a Marie Security Guard battalion thought Russia, and large swaths of Western and Eastern Europe and writes of camaraderie in service between men and women.

In Afghanistan, women lead in combat and in attempts to win “hearts and minds.” Capt. Kristen Griest and 1st Lt. Shane Haver become the first women to graduate from the Army’s Ranger school in 2015. Almost immediately, Congressman Steve Russel (R-Oklahoma) a former Ranger qualified infantry officer requests the female graduates’ training records. Sue Fulton, a West Point alumnus, responds with a request under the Freedom of Information act to see Congressman Russel’s Ranger School Records.

Record of Gallantry

It’s My Country Too presents essential research and upheaves women’s history of gallantry that’s been obscured and overlooked. While the research would be enhanced with the inclusion of an index, the stories themselves are essential to U. S. history. These accounts deserve integration into our national narrative.

Military women serve within the hegemony of prevailing systems because it’s impossible to fight on all fronts at all times and because it takes a critical mass of events to prompt institutions to change. Women have historically acquired much of their power based on their relationships with men, so many women are adept at silently sacrificing for others. Men do have a history of nobly sacrificing themselves for family and country, but have never lived in institutional and cultural expectations of quiet invisibility.

The stories collected by Bell and Crow provoke a vision of the rancid thread that runs throughout our history. The importunity in the stories of service and sacrifice also pulls a more honorable thread through the cloth of our culture.

About the Author of the Review

Amy Lou Jenkins writes about people, places, and ideas. She has taught writing at Carroll University, Milwaukee Area Tech College, and conferences and workshops, including NonfictioNow/ Iowa Writers Workshop and Write by the Lake/University of Wisconsin Madison. Find her essays and stories in literary journals and anthologies including, The Florida Review, Flint Hill review, Leopold Outlook, Earth Island Journal, The Maternal is Political, and Women on Writing. Jenkins authored Every Natural Fact; Five Seasons of Open-Air Parenting. Her honors include US Book Award, Living Now Book Award, Ellis Henderson Outdoor Writing Award, and XJ Kennedy Award for Nonfiction. She pens a quarterly book review column for the Sierra Club. Jenkins and her husband split their time between Wisconsin, Arkansas, and their travel van. Unless it’s so cold it hurts, she’d rather be outside.