Writing Beyond the Anecdote: Crafting a Resonant Personal Essay

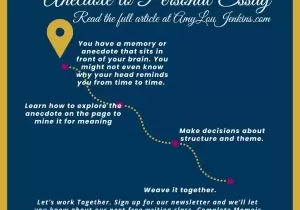

Transform an anecdote into a personal essay. For many writers, the personal essay begins with a vivid slice of life experience that hints at deeper significance. It might be a family story or an event that your mind pulls up for you to turn over from time to time. Use the anecdote as a vehicle for exploring universal human truths in a way that fosters connection with readers. Here's a roadmap for writers to move from anecdote to thematic personal essay:

First Paragraph of "Once More to The Lake"

One summer, along about 1904, my father rented a camp on a lake in Maine and took us all there for the month of August. We all got ringworm from some kittens and had to rub Pond's Extract on our arms and legs night and morning, and my father rolled over in a canoe with all his clothes on; but outside of that the vacation was a success and from then on none of us ever thought there was any place in the world like that lake in Maine. We returned summer after summer--always on August 1st for one month. I have since become a salt-water man, but sometimes in summer there are days when the restlessness of the tides and the fearful cold of the sea water and the incessant wind which blows across the afternoon and into the evening make me wish for the placidity of a lake in the woods. A few weeks ago this feeling got so strong I bought myself a couple of bass hooks and a spinner and returned to the lake where we used to go, for a week's fishing and to revisit old haunts.

Mining Your Anecdote for Deeper Meaning

Anecdotes contain layers ripe for exploration. After relating your story, identify the specific moments, details, decisions, emotions, or perspectives that continue resonating with you. Interrogate these echoes through freewriting and questions like:

- Why did this experience impact me?

- What life views or beliefs did it reinforce or contradict?

- How did my perspective evolve?

- What does it make me feel?

- Why does it still make me laugh or cry or remember it?

Let the anecdote be the gateway to unearthing broader meanings and themes.

Example: E.B. White's "Once More to the Lake" starts with a family trip but evolves into reflections on the passage of time and the cycle of life.

Get out your paper and pen or pencil (Write rather than keyboard.)

- Write your anecdote

- Freewrite as suggested in the above paragraph.

Identify a Unifying Theme

Personal essayists don't state a thesis like academic writers, but their narratives are centered around a clear theme, core question, or area of exploration. For example, Nora Ephron's essay "A Few Words About Breasts" humorously returns to her physical insecurities as an entry point into interrogating societal pressures on women's body image. Scott Russell Sanders' essay "The Inheritance of Tools" uses his family's handyman legacy as a lens into inquiring about the role of physical labor and ownership in 20th-century masculinity. The theme revealed through your anecdote provides perspective and purpose.

Example:

James Baldwin's "Notes of a Native Son" uses personal anecdotes to illuminate the cultural disinheritance experienced by Black Americans with a history of slavery in their families. Baldwin's recounting of his tumultuous relationship with his father serves as a lens to examine broader themes of racial identity, societal alienation, and the enduring impacts of slavery. By intertwining intimate firsthand experiences with historical context, Baldwin speaks to the universal struggle for identity and belonging amidst a legacy of oppression. He makes history personal.

Build Out with Research, Examples, and Introspection

Using your identified theme as a guiding light, build out the narrative with additional supporting anecdotes, reflections, facts, quotes, descriptions, and thought-provoking questions—all working together to illuminate your main area of exploration.

The essayistic "wander" through various paths is part of its intellectual and emotional discovery process. You’ll freewrite, research, and seek out related experiences. Then, you will include the information that supports your chosen theme. Make decisions.

Example:

Annie Dillard's famous personal essay "Total Eclipse" recounts her experience witnessing a total solar eclipse. The experience serves as a lynchpin to explore larger themes about human perception, existential questions, and our place in the universe. Here are some examples from the essay:

Dillard uses evocative details to immerse the reader in her experience, which become a gateway into deeper philosophical terrain. The scene creates a mood. It's lyrical.

"The eclipse was grained; it cast arcs of ruby on the land...It strolled on...growing smaller by immense, easier, no-hurry strides."

Language

The language connects the tangible experience to the more abstract philosophical territory she explores.

"The second before the sun went out, we saw a wall of dark shadow...At that moment, a piece of sun was going, and from the backside of the darkening world she continued unperturbed."

Ultimately, Dillard arrives at insights about the paradoxes and mysteries within human existence. She hints at what happens when we experience connections to phenomenon larger than ourselves:

"These clouds, appearing improperly brilliant...seeming to unweave, and reweave intricate fresh folds and to rumple...until the sky was no longer quite the same bright blue as before."

By grounding heady themes within a vividly rendered personal account, Dillard makes the metaphysical tangible. She turns a passing phenomenon into a lens on the enduring enigmas of life.

,,If you've been writing on paper for a while and haven't found your momentum, write again and this time use your keyboard. Or perhaps change your location.

Eventually you must decide on a theme and a structure. Then you take all that freewriting which is prewriting and consider how to weave your essay. By this point, even though it can be difficult, the art and story begin to take on a life of their own.

Search for What's Universal

The most powerful personal essays use individual stories to illuminate universal experiences, history, facts, and wisdom. Throughout the writing process, analyze your narrative in search of common human struggles, emotions, realizations, and questions that could transcend your own specific circumstances. How do your insights and hard-won perspectives help readers gain deeper self-awareness and empathy? Let these universal connections be your essay's philosophical undercurrent, flowing beneath the personal narrative.

"There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says "Morning, boys. And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes "What the hell is water?"

Example:

In his famous commencement speech turned essay "This Is Water," David Foster Wallace uses daily frustrations and challenges to underscore the importance of cultivating compassion. He's relatable.

He opens with an anecdote about the drudgery of everyday banalities like running errands'

"There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says "Morning, boys. And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes "What the hell is water?"

Putting the Anecdote to Work

This sets the stage for Wallace to argue that the most crucial realities of our lives are often the ones that are so ubiquitous we become blind to them, like the water the fish live in.

He uses mundane universal experiences like having to deal with mind-numbing bureaucracies and automated phone systems:

"This appalling cluelessness and depersonalization...is so routine...that they barely even register anymore."

Wallace contends that it's stories like these - the "petty, frustrating crap" of daily existence - where the real opportunity for transcending our natural self-centeredness resides. If we remain mindfully aware of how our default perspective entraps us, we can learn to break free:

"It is about making it to 30, or maybe 50...and getting real and staying true."

By making the universal agitations of adulthood so viscerally felt through his examples, Wallace makes a powerful case for the urgent need to combat our natural self-absorption through serious intentional discipline. His essay uses the drill bit of daily mundanities to cut a path toward the liberating mindfulness and empathy he advocated. He makes a case for compassionate connection to others

The Opposite is also True

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, by Roxxane Gay

This essay collection/memoir contemplates societal demands and expectations related to appearance, women's pleasure, and consumption. Everything is touched by the role of sexual abuse in her own life. Every subtheme exists within the subtheme of control of women's bodies.

Both Gay and authors like Jenkins (sorry about talking about myself here) and Leopold employ scenes ("showing") and analysis ("telling about your evolving thoughts") throughout their works. However, they differ in the works described previously in the backbone used to structurally organize their narratives. Jenkins and Leopold (in Part 1 of Sand County Almanac) tend to build their essays around an unfolding storyline, using scenes and actions as the core framework, which they then supplement with narrative telling.

In contrast, Gay structures Hunger primarily around her thematic narration - her reflective commentary on the subject matter serves as the central organizing thread, which is then illustrated by interwoven scenes and analysis. Gay's approach could be considered more academic in nature. Ultimately, it is a stylistic choice authors make in terms of whether to scaffold their work on an episodic storyline or thematic exposition. (You can find essays by Jenkins and Leopold that also use a thematic narrative as a structural scaffold, and these tend to be more academic.)

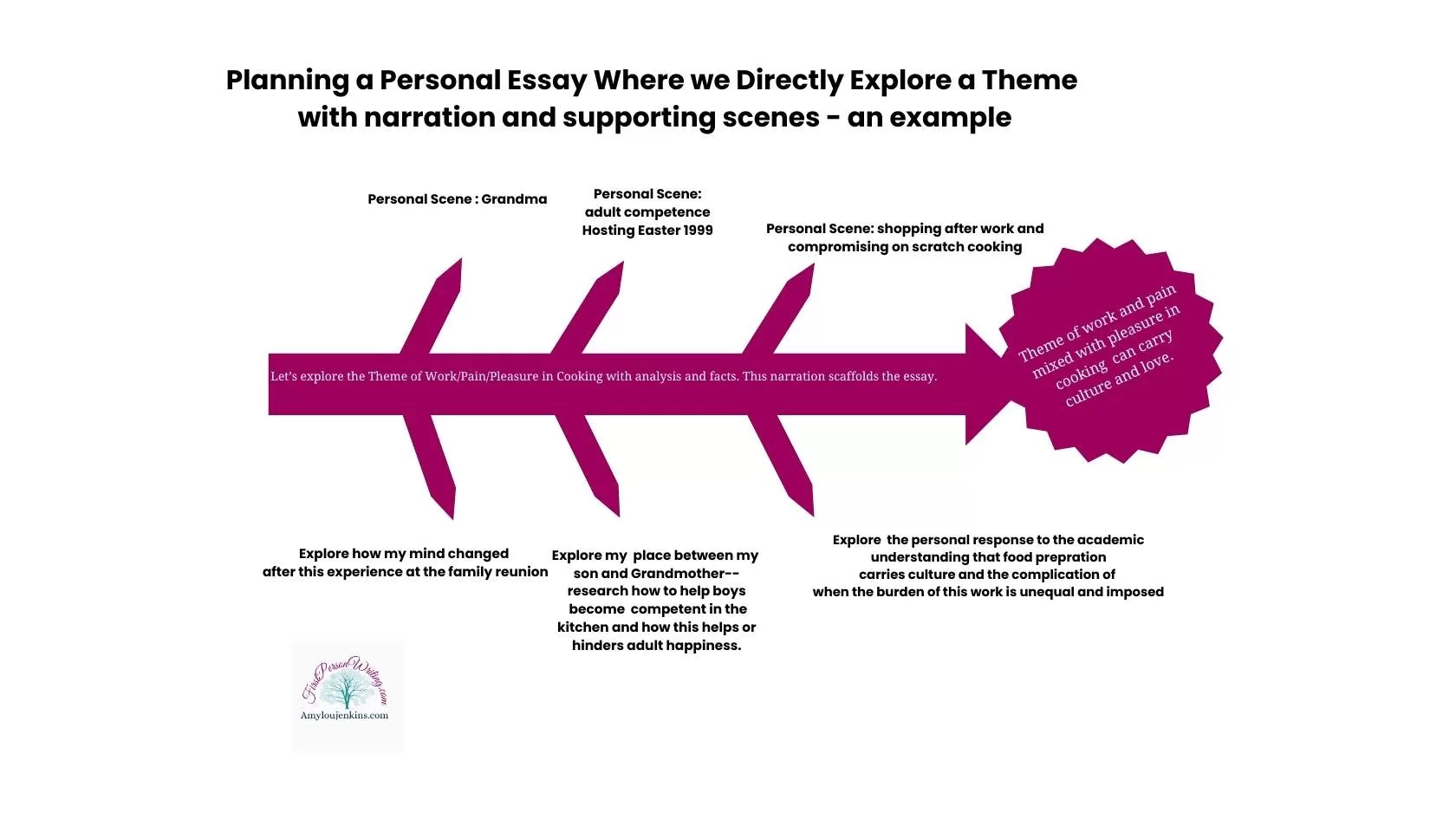

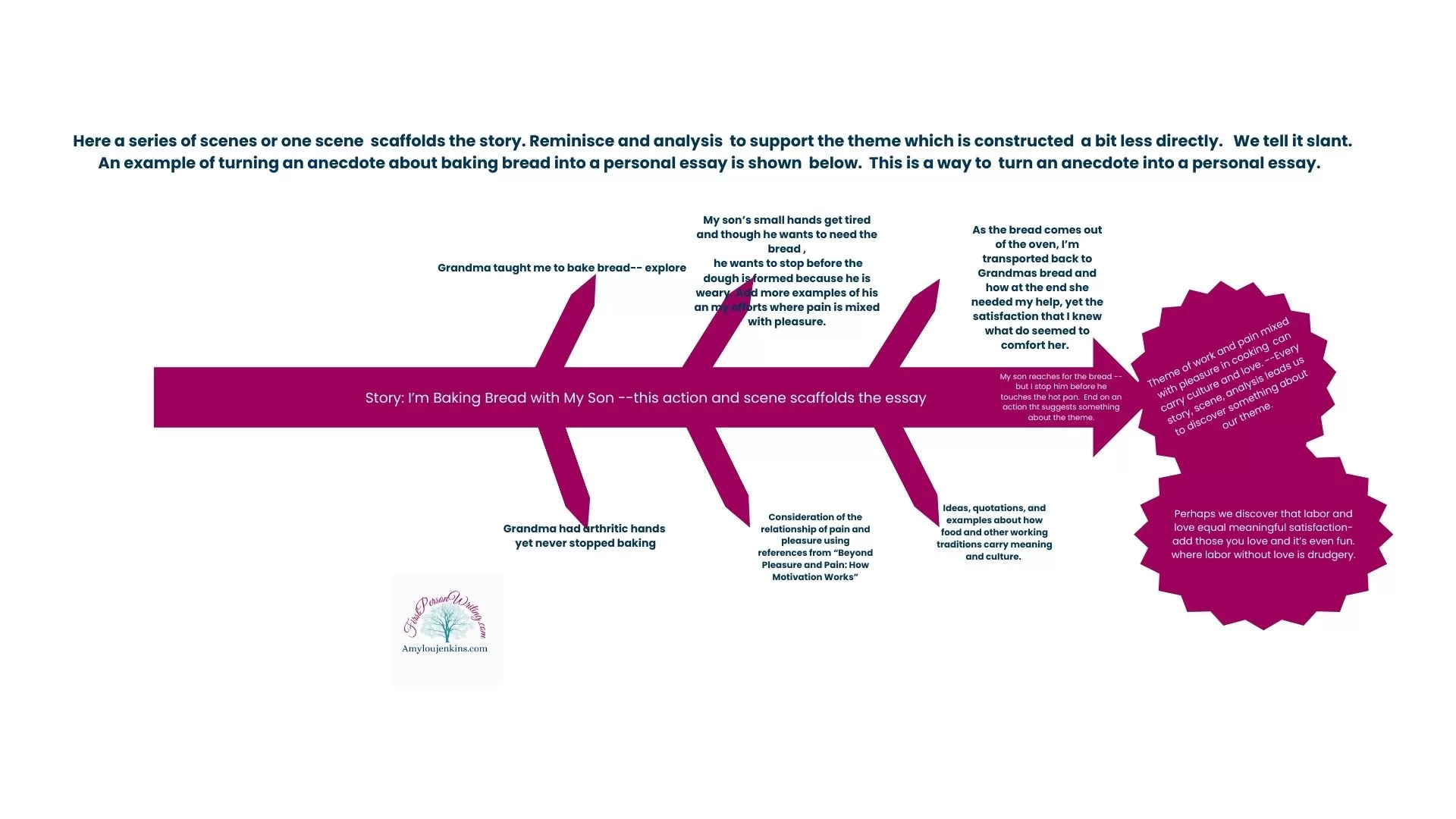

Another Way to See Structure

Perhaps these graphic representations will show you the differences. Build your essay on story (showing) Here you begin in a scene and scenes are your scaffold. Your anecdote may be the spine of your story. Conversely, build your essay on telling (narrative). Your anecdotes can illustrate your narrative. Either way, show and tell.

Your Specific Experience Illustrates Universal Themes

By investing anecdotes and individual experiences with thematic exploration, contextual knowledge, emotional resonance, and human universality, writers can evolve engaging personal essays. You can connect to your reader through time and space. It’s like magic.

Build Your Personal Essay

- Write out Your Personal anecdote or story idea

- Mine adjacent memories, facts, ideas, places and find the personal essay essay that wants to be told. Remember you find it while writing -probably not in your head. At this point, you are likely not writing an essay. It's an essential idea dump.

- Select a theme-there may be more than one that would work put pick one.

- Decide on a structure. Consider the graphics above.

- Use your prewriting and decisions to guide you as you craft your essay.

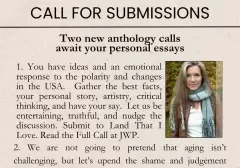

1 thought on “From Anecdote to Personal Essay”